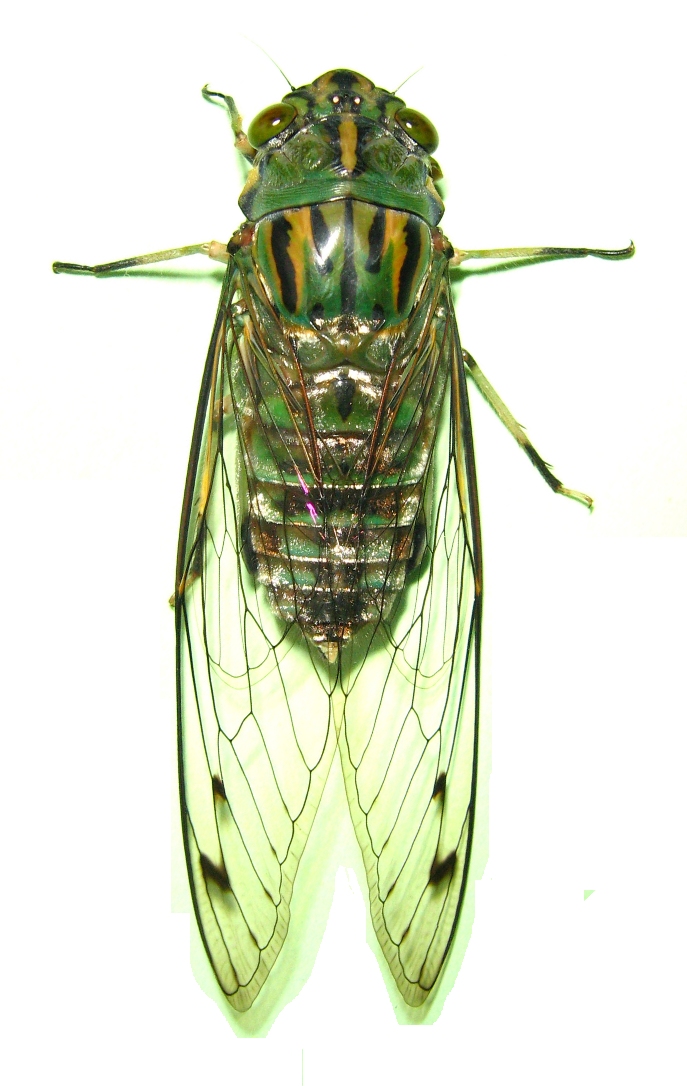

Chances are, you have what is called a cicada ("sick- ay- dah", "sick- ah- dah"). This is not technically a true "fly", but rather a distant cousin of aphids. Normally, these sit up in the treetops, singing with a steely whine during the hot days of summer. They are also known as "harvest flies" in the eastern U.S., and by a whole grab bag of nicknames around the world depending on the species and the locale. Usually they are a kind of camouflage color, as shown here, but some species are very brightly-colored. And, the male cicada is the only insect in the world that is capable of literally screaming. Before you haul out the economy-sized can of Raid (or before you empty it the rest of the way), relax. Cicadas do not bite, neither do they sting. To humans and animals they are pretty much harmless. They won't do much (or any) damage to your garden, either. Your beans, corn and roses are safe-- cicadas specialize in trees. The young cicadas live underground, drinking sap from tree roots, and eventually they dig themselves out, climb up the tree trunk, molt (shed their skin) and emerge in the winged form. The winged cicadas fly up into the treetops, occasionally sticking their soda-straw beaks into the twigs they're perching on and drinking the tree sap between songfests. I was inspired to put up this page by this post from a very puzzled Georgian who had gotten one of these bugs in his house:

|

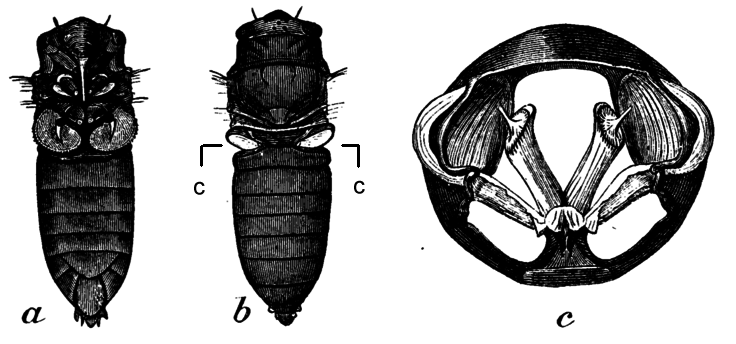

From Wikipedia Cicada sound-producing organs and muscles. (c), cross-section of male cicada's body, showing the tymbals, tymbal-muscles and sound chamber |

Male cicadas have a pair of "tymbals" in either side of the body which are similar to those little cricket-clickers you might have played with as a kid. Inside, as you can see in the cross-section, there are muscles attached to the tymbals and a big hollow chamber to amplify the sound. The summary of Wikipedia's scientist-speak is that the cicada clicks these tymbals using the internal muscles. It can move them much faster than you can squeeze your fingers, so the series of clicks comes so close together that it sounds like a whine or buzz to us. Some cicadas can get up to 120 db (as loud as a jet engine) so we're talking a loud whine.

Since it's the males, it is of course a courtship song to call in the females. Since there are many different species of cicadas, each kind has an individual pattern to its song.

Normally, the cicadas all stay up in the trees courting. But occasionally, one winds up within reach of a human or other hazard (like a door jamb). If the cicada is frightened, the male has a fallback use for its tymbals-- it screams.

Oh, lordy it can scream. It screeches and squawks and howls and skrawks like a cat in mortal

agony. If its wings are free, the cicada also buzzes furiously. The flapping and the

squalling is plenty enough to get all but the most stout-hearted to drop the bug immediately.

But it's all bluff. As I mentioned, cicadas cannot bite or sting, so their only option is to

make a hellacious racket.

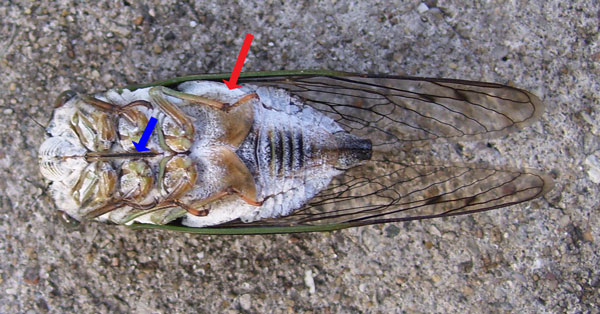

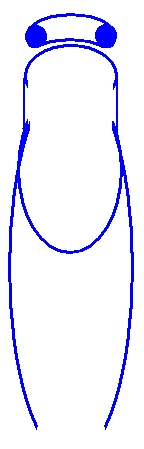

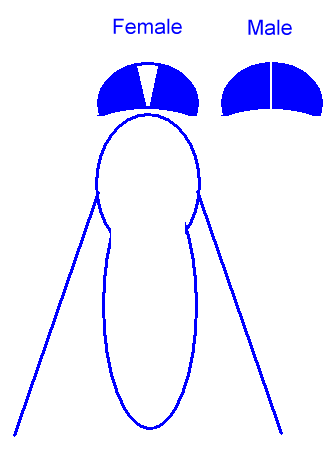

Aside from the screaming, it is easy to tell the male cicadas apart from the females-- just flip them over and look at the underside.

Male cicada. He has two big covers on his underside which protect the tymbals (red arrow)

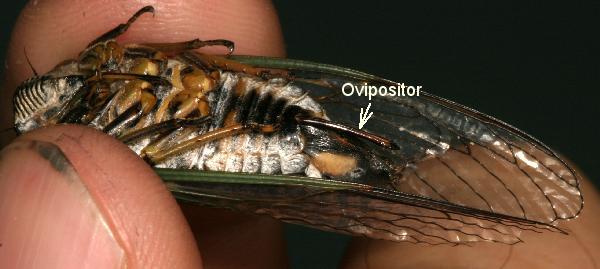

Female cidada. She does not have the two big flat panels on her belly. Instead, she has a

long

pokey sticker ("Ovipositor").

Don't worry-- this is not a stinger! Instead, she uses it to stick her eggs into tree twigs.

When they hatch, the tiny baby cicadas (called "nymphs") wriggle out of the twig, drop to the

ground and dig down until they find a tree root to latch onto.

More Comments About Cicadas

My mother was terrified of bugs, but she read somewhere that kids learn such fears from their parents at an early age. She was alone in the house with me and needed someone to wrangle stray bugs for her, so when some insect appeared, she would grit her teeth and point and say, "ohhh, look at the nice bug!" It worked. I remember coming home from kindergarten one day, and she sent me after a Giant Water Bug that was lounging by the back slider door. The thing was nearly the size of my (6-year-old) hand. It looked pretty fierce, so I picked it up by its edges (so that it couldn't reach me to bite me) and carried it to the nearby vacant lot for eviction.

In fact I adored bugs, the bigger the better. Cicadas were some of the biggest bugs around my neighborhood and so qualified as big game. I'd have to wait until one sang from a tree that I could climb, then clamber up there ever-so-stealthy, slowly reach my hand out, and grab the cicada.

They only look slow. These common green "dog-day cicadas" will take off like lightning at the slightest shake of the branch. I once saw a house sparrow trying to catch one. The cicada was flying in great up-and-down arcs like a roller coaster, with the bird flapping madly to try to keep up, and failing miserably. The bug totally dusted the bird.

Once I lucked into a female cicada who was on the branch of a bush right at eye level. She couldn't scream, of course, but when I caught her she buzzed her wings. I held her between my thumb and forefinger, leaving her wings free as I carried her across the street to my house, and by the time I had gotten across, my fingers were numb. It was like holding a powerful little engine. Think Golden Snitch from the Harry Potter books.

A Gallery of Cicadas

17-year Cicada from eastern U.S. |

Cicada orni |

"Green Grocer" from eastern Australia. |

Dog-Day Cicada |

Golden Drummer Cicadas from eastern Australia |

Zammara Cicada - Costa Rica |

A Massive Cicada from Borneo. |

Important: How to Tell A Horsefly From A Cicada

|

Horsefly |

1) Wide, "hammer" head with small eyes on each side.

1) Wide, "hammer" head with small eyes on each side.

2) Wings usually extend far past end of body 3) Wings point straight back along body, "tented" over it |

1) Head narrower, rounder, "helmet head" with large eyes taking up most of the head.

1) Head narrower, rounder, "helmet head" with large eyes taking up most of the head.

2) Wings barely extend past end of body 3) Wings sit at an angle, like the swept wings of a fighter jet, and in a flat plane |

Cicada - face on.

Notice the bulbous "nose" with its ridges- another classic cicada feature

Although horseflies can get to nearly the size of cicadas, they are not harmless. They are (in)famous since ancient times for their bite.

Again, this is a male-female difference. In this case, it is the females who bite. Like mosquitoes, they need a blood meal in order to lay their eggs.

Horseflies also come in a wide variety of species and colors. Many are upwards of an inch long, although the beloathed deer fly of the eastern Unites States is one of the smaller of the family. Some of them have gorgeous, iridescent eyes. That's their one redeeming feature, and best viewed after swatting them.

A Rogue's Gallery of Horseflies

Western Horse Fly |

Black Horse Fly |

Giant Dark Horse Fly |

I highly recommend you read the full blog post about the Giant Dark Horse Fly. The comments are brilliant and fully describe the woe that horseflies can bring.

When I was stationed at an Army base in the U.S. South, I periodically encountered two types of horseflies-- the usual grey one that you find in the eastern U.S. which has the rainbow band in its eyes, and a couple of times, the black horsefly shown above. The picture does not do the black horsefly justice. These suckers are fully an inch long and look like the Darth Vader of flies. The mechanics in the hangar had learned that I was into bugs, so one time they presented me with one of these Darth Vader Horseflies that they had killed. I happily took it home and encased it in a clear dome of plastic with my embedding-resin kit. Makes a great paperweight.

My other encounter with one of these horseflies was one day at first light as my company and I were all waiting around for morning PT formation. (PT stands for "Physical Training" = Army calisthenics). The sun wasn't up yet and it was pretty dim. Through the dim light I suddenly noticed a Darth Vader Horsefly sitting on the cheek of one of my Army coworkers.

I had a quick debate as to whether I should just let it bite her. She had always been standoffish to me; apparently decided to dislike me on sight, and once even told me to my face that "she just didn't like me."

But, I decided that in spite of that, I was a decent and honorable soul, and shouldn't just let it bite her, so I should kill it. It was a big fly as I mentioned, and would need a lot of force to kill it, so I wound up to deliver it a mighty whack before it got its beak into her.

About mid-swing I realized that I was on my way to giving my coworker a roundhouse smack in the face that would probably knock her block off, and at the last minute put on the brakes. So my hand landed gently on her cheek, pressing the horsefly into her skin. (Her cheek was quite soft as I recall.) Of course this didn't hurt either her or the fly. When my hand bounced off again the fly, rather disturbed at all this, flew away. She stared at me with an expression of shock. My coworkers all turned and said, "why did you slap [name redacted]??" I tried to explain that she'd had a horsefly on her cheek, but of course the guilty creature was long gone, so I don't know if they entirely believed me.

I guess it worked out all right, though, as she didn't get bitten, and I didn't get hauled into a court-martial for assault and battery on a fellow officer.

A Horsefly Trap Worth Trying

While wandering around the Web looking for pictures of horseflies, I stumbled across this page. The apparatus is a trough on legs made of scrap lumber, covered with black plastic that drapes over the sides, and is filled with a soap-and-water mixture. (Tip: soapy water drowns insects almost instantly.) Two plexiglass panes are set at 45-degree angles above the pool of soapy death.

The principle is that horsflies see the large dark object and think it might be a cow or horse they can bite. They cruise in over its "back" to scout out a landing spot, but collide with the clear plastic plexiglass when they do so and tumble down into the water to die.

He has further details, and dimensions, on the page. Check it out.